SWE-Star: Best-in-Class Agentic Coding Models

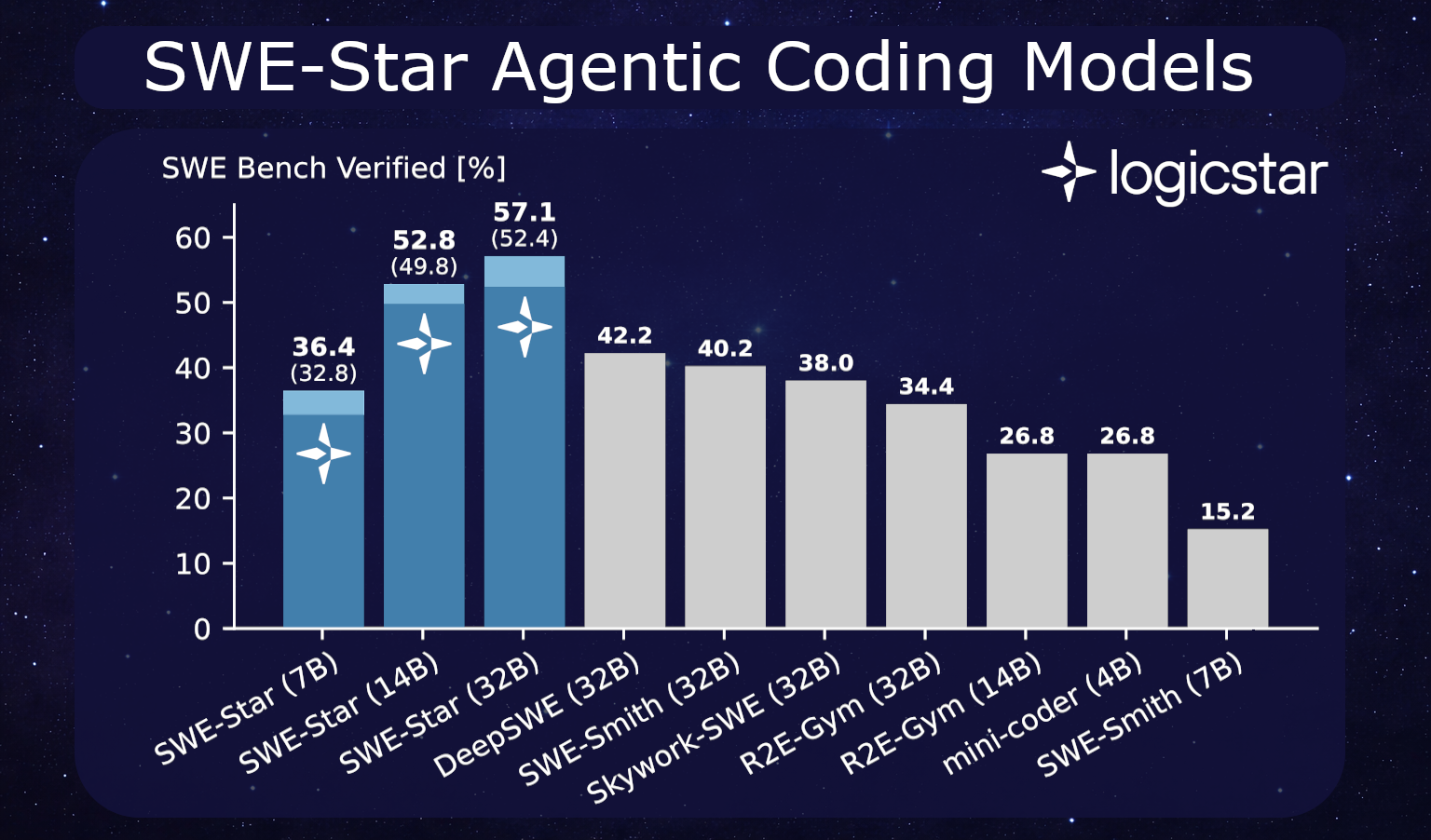

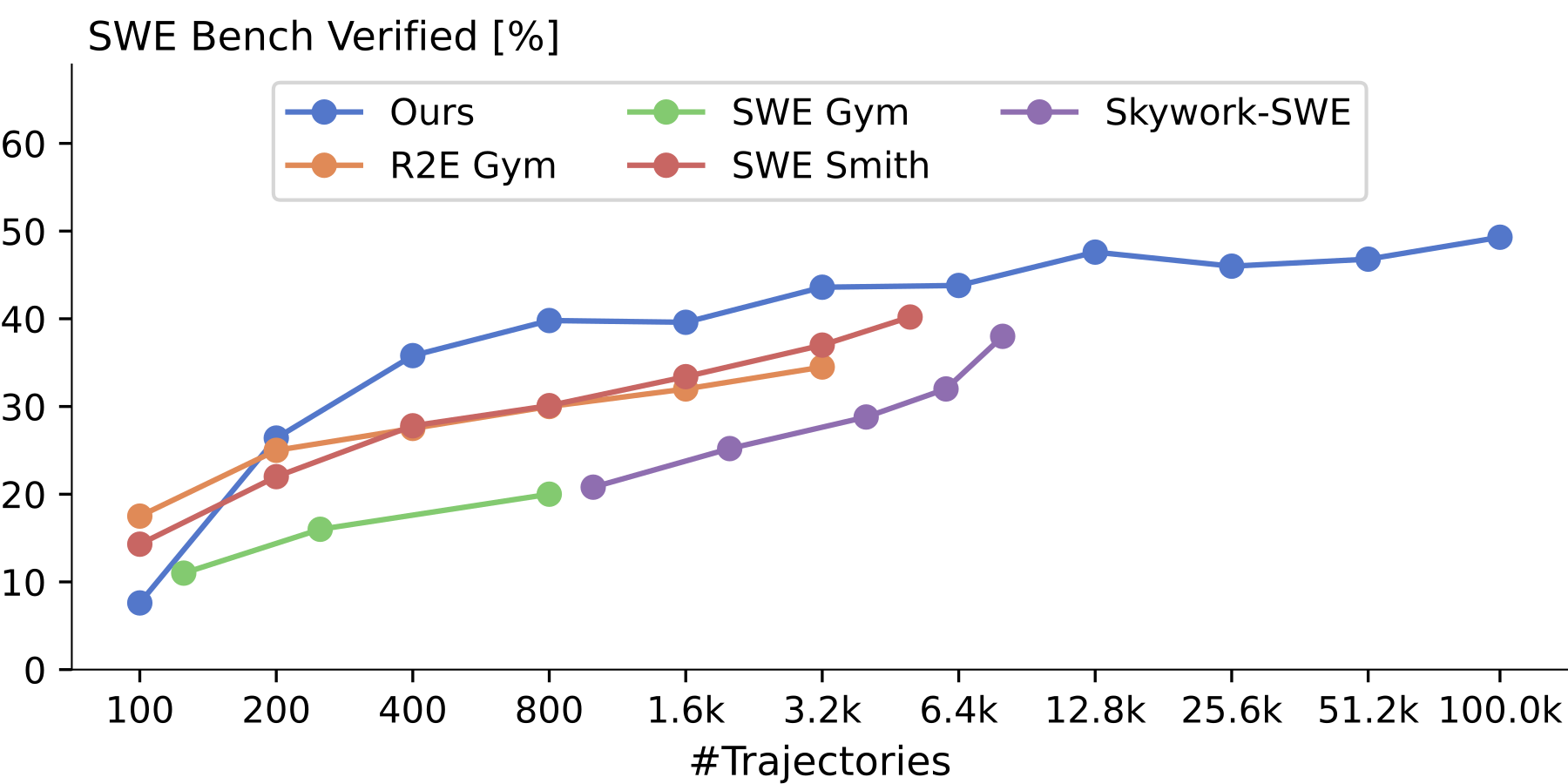

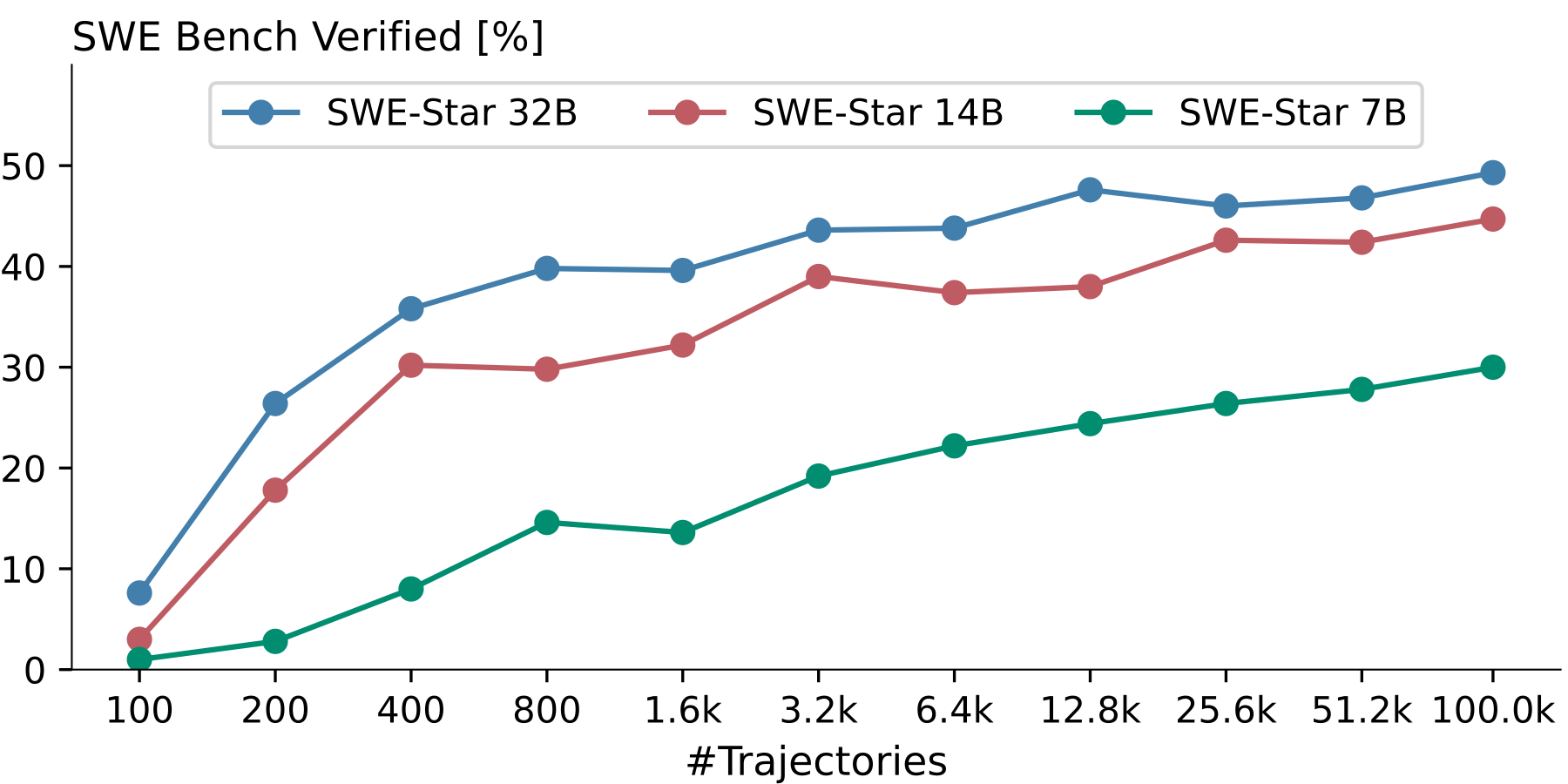

We release the SWE-Star model family: a 7B, 14B, and 32B model based on Qwen2.5-Coder variants and trained on a dataset of 250,000 agent trajectories. Our largest model, SWE-Star-32B, reaches 57.1% on SWE-Bench Verified, setting a new state-of-the-art among open-data models in this size class. The 14B variant reaches 52.8%, significantly outperforming other models of its size. Finally, the 7B variant achieves 36.4% without any signs of saturation, showing the promise of even small models. Using only a single attempt instead of the standard OpenHands iterative protocol of at most 3 attempts until a solution is submitted, we achieve a Pass@1 of 52.4%, 49.8%, and 32.8%, respectively

.png)

We generate our dataset using a custom lightweight agent, Devstral-2-Small, and SWE-Smith environments. We used MareNostrum 5 (MN5), a European public supercomputer with 4,480 H100 GPUs, for all data generation, training, and evaluation. In this post, we describe how we scaled agentic data generation, training, and evaluation on its highly restricted HPC environment — no Docker, no outbound internet, and massive parallelism — and how these constraints shaped the system design. We also open-source our full agent scaffold, data generation pipeline, and training infrastructure so other researchers can build on this work on similar clusters.

Ever since the original scaling laws paper, scaling has been the dominant recipe for improving models — more parameters, more data, more compute, at first focused on pretraining, and more recently mid- and post-training.

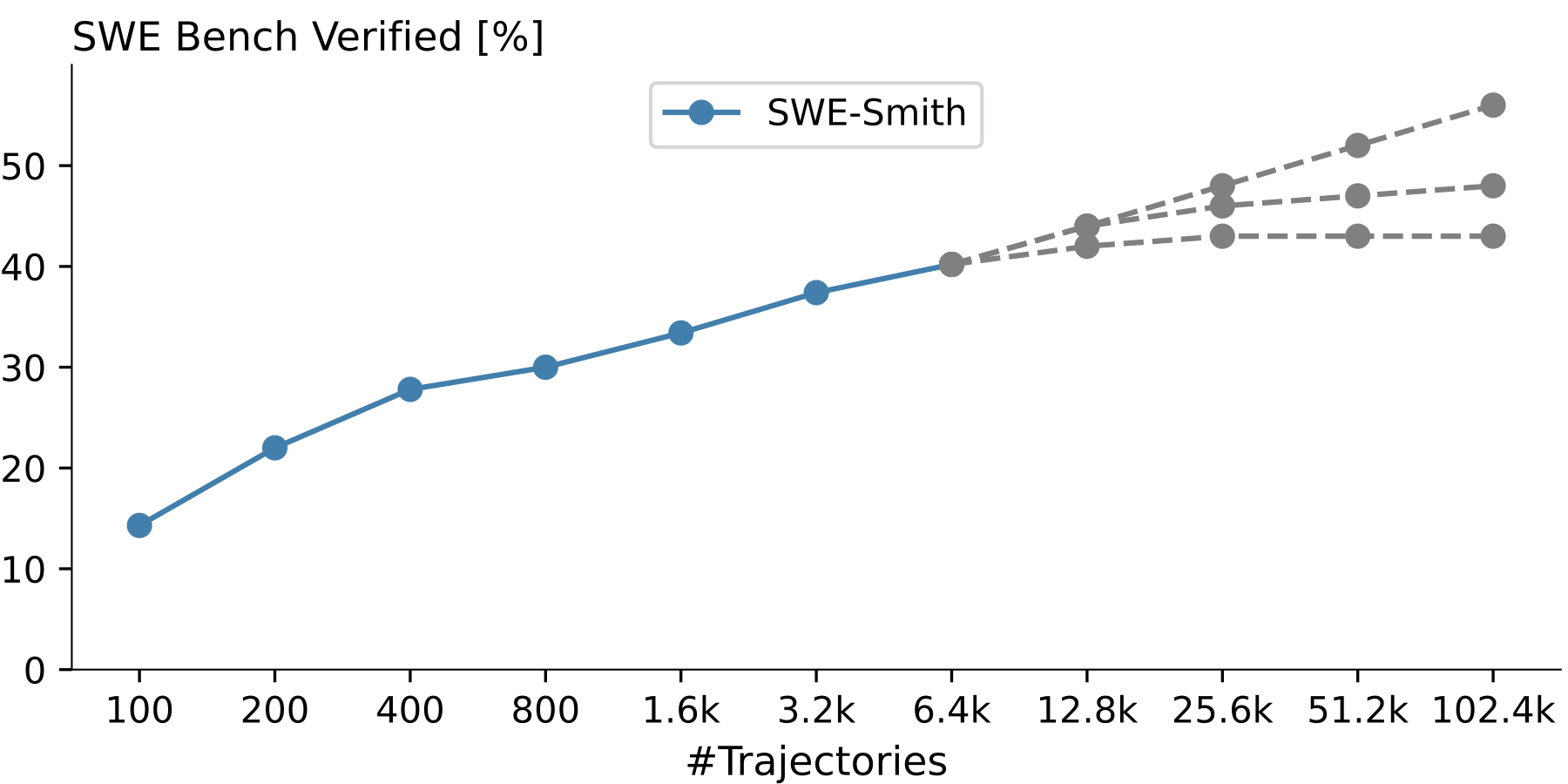

Distilling from strong teacher models is an attractive alternative to scaling post-training because it promises to be a sample-efficient way to let smaller models learn long-horizon reasoning and tool-use behaviors without the overhead of full RL. Over the past year, several works have built SWE-style environments to enable this. Most notably, SWE-Smith introduced a scalable pipeline for injecting bugs into real codebases and back-translating them into realistic but synthetic issues. Using this pipeline, they created 5k agent trajectories using Claude Sonnet 3.7 and observed almost perfect log-linear scaling, pushing Qwen2.5-Coder-32B from 10% to 40%.

With the best open-weight models approaching 70% on SWE-Bench Verified, we asked: How much of their agentic capability can we distill into smaller, cheaper, and easier-to-deploy models using SFT alone?

Infrastructure for experiments at scale

With a single training run on 100k trajectories consuming roughly 4,500 H100-hours at ~4$ each and our intent to run large-scale ablations, we did not want to simply rent a cluster. So we applied for an EuroHPC grant, an EU initiative that provides access to Europe’s largest supercomputers for researchers and startups, including MareNostrum 5, and were awarded 50k hours after just one week.

MN5 offers lots of compute, but it comes with some unique constraints. For historical reasons common in HPC environments, the cluster has no outbound internet access, and the only interface is SSH access to two login nodes. The system is managed by SLURM, and compute jobs run in a highly restricted user mode. This is very different from typical cloud VMs, where you have full system control. In addition, MN5 uses nodes of 4 H100s with 64GB VRAM each instead of the more common nodes of 8 H100s with 80GB each.

This implies:

To overcome these constraints, we built a custom agent scaffold, forked from mini-swe-agent, that supports OpenHands tooling and scales efficiently under MN5’s constraints. Expert models are hosted via SGLang, data generation is orchestrated through SLURM submissions, and post-training is done with torchtune. The pipeline supports massive parallel data generation and hundreds of concurrent training runs for systematic scaling studies.

OpenHands is currently the most popular open-source ReAct-style agent scaffold, providing basic tools for editing and browsing codebases as well as context condensation. While large proprietary models perform reasonably well with minimal tooling, smaller models with limited context windows (e.g., 32k tokens) struggle without structured editing and condensation.

Our design mirrors OpenHands in both tooling and condensation. The agent has access to four tools: think, execute_bash, str_replace_editor, and submit. When the context limit is reached, older observations are masked until the condensed context fits back into the model’s window while preserving space for reasoning and tool calls. We use XML-style tool calls for simplicity, since Qwen2.5-Coder does not support native tool-calling tokens.

Due to MN5’s restricted user mode, each agent runs inside a single-UID Podman container, communicating through two interactive Bash sessions. This differs from common execution-server designs, which require privileged container builds. We translate all str_replace_editor calls into equivalent Bash operations (e.g., first reading a file, editing the file on the host side, and writing it back via cat). A separate dedicated long-running Bash session handles all execute_bash commands.

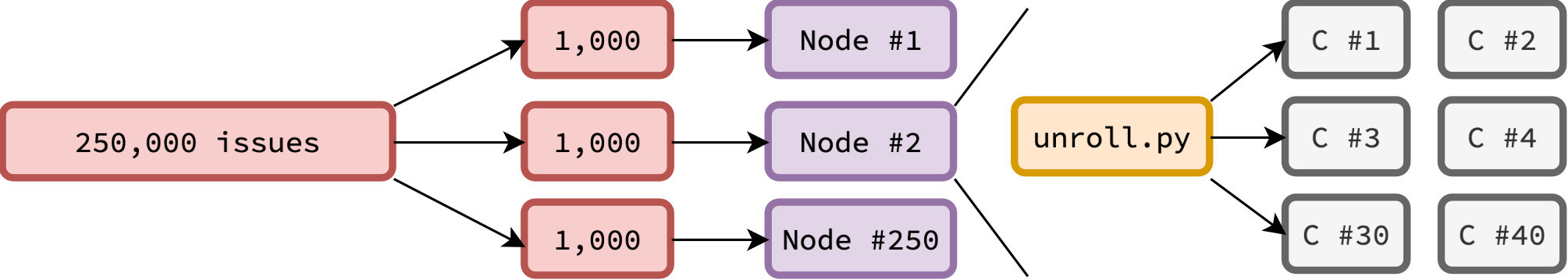

SWE-Smith created 10k problem statements from which they obtained 5k trajectories after filtering. As we wanted to scale to at least 100k trajectories, we first created problem statements for the remaining 40k instances in the SWE-Smith dataset. Then we had to unroll 250k agent trajectories to be left with 100k after filtering.

Because everything had to run on MN5, we self-hosted our teacher models. Shortly before our project began, Mistral released Devstral-2-Small, a 24B model achieving up to 68% on SWE-Bench Verified with their own agent scaffold. In our offline OpenHands setup, we achieved around 60%, which still provides a strong margin over the ~40% baseline we aimed to surpass. Our ablations also suggested that teacher strength is secondary during early scaling.

Devstral-2-Small fits efficiently on a single 4×H100 node (256 GB VRAM) using SGLang. In agentic workloads, the main bottleneck is the KV cache memory. With up to ~100 turns per trajectory, re-prefilling the same prefix repeatedly severely degrades throughput. A full 32k context occupies ~5.4 GB, and we found ~40 parallel agents per node to be a good trade-off between cache reuse and decode batch size. We further used N-gram speculative decoding, which proved highly effective due to repetitive code patterns.

Each node can unroll roughly 200–300 trajectories per hour. Sequentially generating 250k trajectories would thus take over a month — so we parallelized aggressively. With ~200 nodes, the entire dataset can be generated in under five hours. Each node operates independently, making job scheduling and dataset partitioning straightforward:

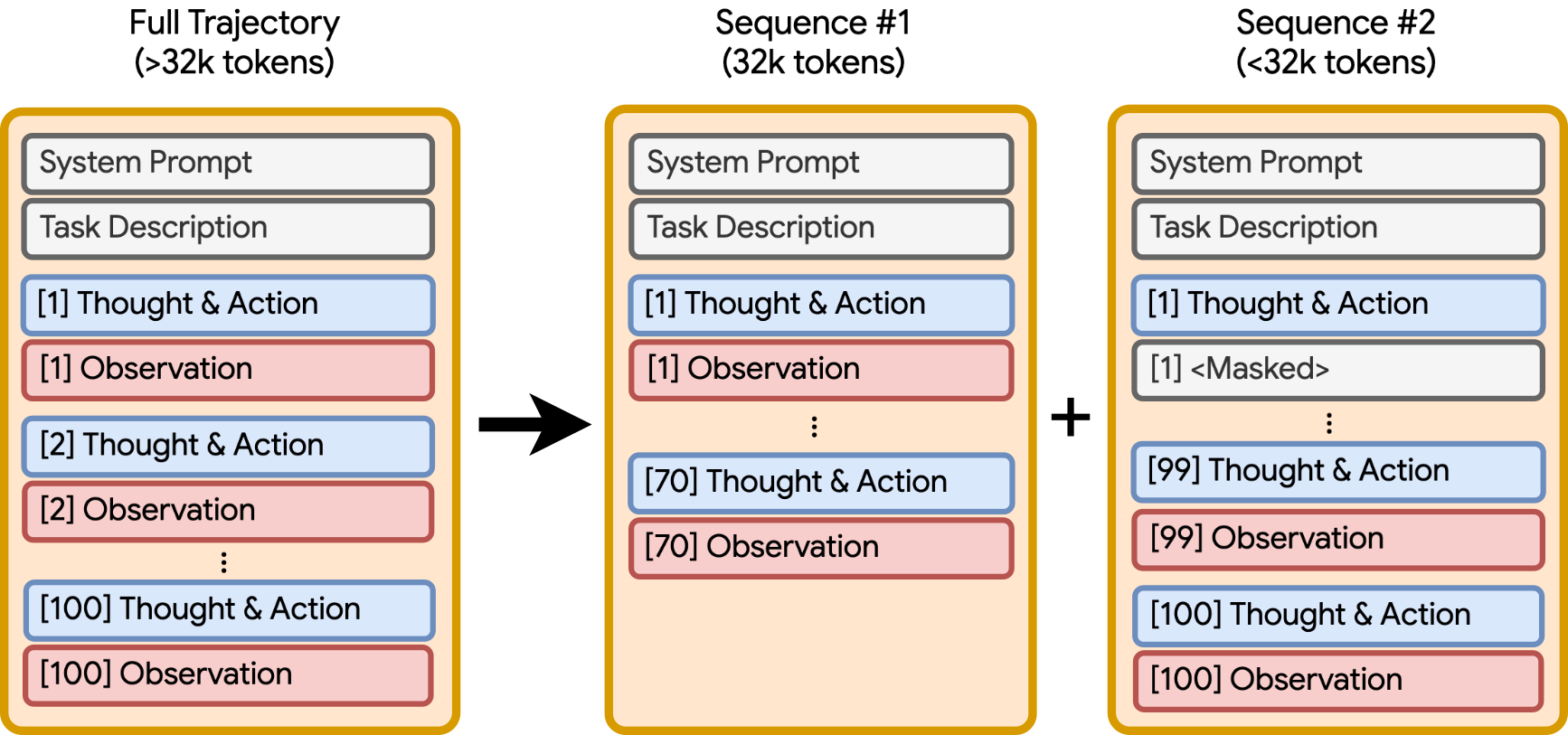

We filtered the 250k trajectories to retain only those that passed the final SWE-Smith tests. Because Devstral-2-Small supports contexts up to 256k tokens while Qwen2.5-Coder is trained on 32k, we segmented long traces into approximations of what the agent would observe under context condensation:

We chose torchtune for supervised fine-tuning due to its simplicity, memory efficiency, and FSDP2 support. Each of the H100, installed in MN5, provides only 64 GB of VRAM, so we trained across four nodes (16 GPUs total) with full sharding of weights, gradients, and optimizer state in bf16. All models used a learning rate of 5e-5 with a cosine schedule. Activation checkpointing and offloading were necessary to support full 32k context training under these memory constraints.

Interestingly, we observed much more efficient initial scaling compared to SWE-Smith, despite similar teacher performance. However, this quickly saturated, reaching about 40% SWE-Bench Verified resolution rate with only 800 trajectories for the 32B model. From there on, scaling continues after a short plateau at a significantly slower rate.

Interestingly, these dynamics are relatively consistent across model sizes, all realizing quick improvements before plateauing at around 800 trajectories and growing more slowly from ~1600 trajectories onward. The slope of this second stage varies, though, with the 14B model coming surprisingly close to the 32B model, given sufficient training data, and even the 7B model showing no clear signs of saturation, even at 100k trajectories.

We hypothesize that these training dynamics are caused by two different training regimes. In the first regime, the model mostly learns how to use the available tools and agent framework effectively. In the second regime, the model then actually learns how to resolve issues more effectively.

.png)

Analysing how resolution rates change with more attempts, we see a ~15% point improvement with just 3 attempts, and our 32B model reaching 75.5% Pass@16. This indicates that even these small models can solve most tasks with relatively few attempts but lack the high-level guidance to choose the right approach every time. This is a promising sign for a potential RL post-training stage, as it shows that the models did not suffer a mode collapse

Concurrently with this work, multiple other groups also scaled SFT for agentic coding, achieving slightly worse result with the same context window and comparable results with larger context windows and better base models: Wang et al. create more issues by translating them across repositories achieving 52.2% and 22.8% (compared to our 57.1% and 36.4%) on SWE-Bench Verified, with their 32B and 7B models, respectively. Tao et al. use a more involved SFT approach, masking incorrect steps and the stronger Qwen3 family as base model with a 4x larger 128k context to achieve 52.6% and 42.2%, with their 32B and 8B variants, respectively. Shen et al. introduce soft verification and build on Qwen3 to achieve 49.5% and 31.7% at a 32k context with their 32B and 8B variants, respectively.

As we scaled training data 20x compared to SWE-Smith and improved performance by over 15% points on SWE Bench Verified, we quickly observed the near log-linear scaling, described in earlier work, to saturate with improvements beyond ~40% becoming super-exponentially harder.

We hope our work helps demystify large-scale agentic coding distillation and encourages more open experimentation in this space. To this end, we release our training and data generation pipeline on GitHub and our models and dataset on Huggingface.

If you find yourself wondering: Is masking observations really necessary? Is rejection sampling actually helpful? Are we bottlenecked by environment diversity or trajectory quality? Does unrolling each task multiple times help or hurt? — These are exactly the questions we explore in part 2 of this blog post.

Authors: Christian Mürtz & Mark Niklas Müller

A big thank you to Christian Mürtz, who explored this topic during his Master's Thesis at LogicStar, together with our CTO Mark Müller.

This project was built using MareNostrum 5 ACC, one of Europe’s largest operational GPU clusters with 4,480 H100s. All European researchers and startups can apply for 5,000–50,000 H100-hours via EuroHPC AI Factory calls to reproduce, extend, and improve this work. The grant process is fast and straightforward!

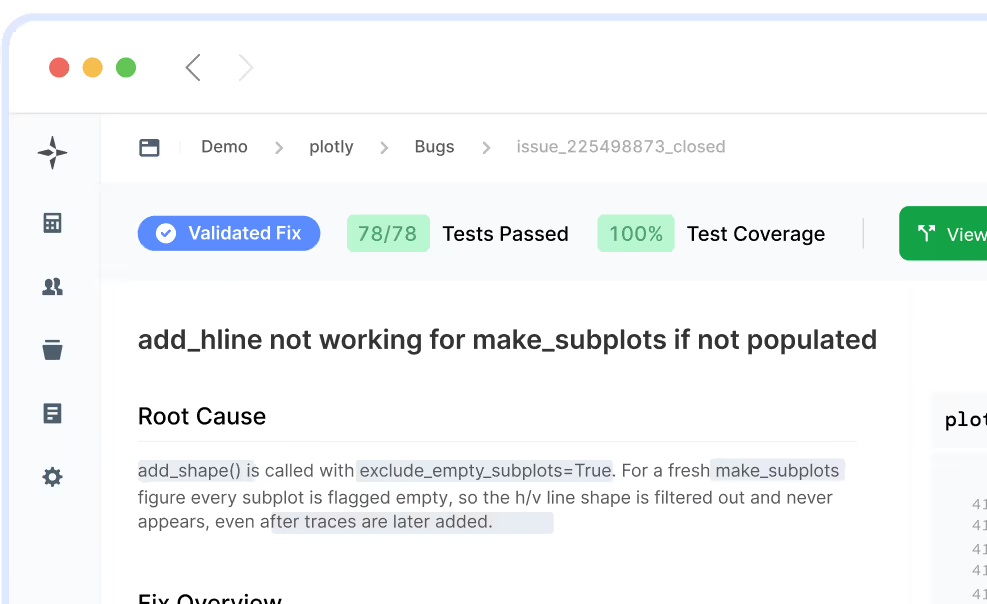

Join the beta and let LogicStar AI clear your backlog while your team stays focused on what matters.

No workflow changes and no risky AI guesses. Only validated fixes you can trust.